The process of hedgelaying or coppicing is a fantastic opportunity to establish new young standard trees in our hedges. Our hedgerows now have far fewer trees than they have done historically, but fortunately we are in a position to help increase them again. Hedgerow trees make a huge contribution to the beauty of our landscape and can have benefits for agriculture, wildlife, and to the wider environment. Of course the decision about how many hedgerow trees to establish will be down to the landowner, but the following information might help.

Establishing hedgerow trees

Hedgelaying and coppicing are the perfect opportunity to establish new hedgerow trees. This can be done in two ways:

1. Leave suitable stems standing when you lay

By selecting suitable stems to leave when laying, you establish new young trees with no financial cost. Trees may have developed naturally in the hedge to be laid or have been planted along with the hedge if a hedge is being laid for the first time. These trees, by the nature of how they have grown up with the hedge, will often have a great shape naturally and need little work to become a great hedgerow tree.

Naturally colonised trees have the added benefit of preserving the genetic diversity present in your local tree populations, genetic diversity being a crucial defence of any species against the unknown threats of the future.

2. Plant new trees in gaps, or slightly out of the hedge line

Gaps in hedgerows can be planted up with new hedge plants when a hedge is rejuvenated but small gaps also provide an opportunity to plant a hedgerow tree. If there are no gaps, trees can be planted just outside of the hedge line.

The benefits of hedgerow trees

- Hedgerow trees can increase the diversity of a species-poor hedge. You can even plant new species which will blossom and fruit at different times and support a wider range of wildlife.

- Hedgerow trees can provide a stable store of Carbon without taking up valuable farm land. Whilst a hedge managed on a cycle will be periodically rejuvenated, cycling much of the carbon it holds, hedgerow trees can be a more permanent feature so will store sequestered carbon for as long as it lives, potentially hundreds of years.

- Hedgerow trees can provide added wind shelter for livestock, as well as

- Over half of the priority species associated with hedges are dependent on hedgerow trees*. They provide song posts and territory markers for many important bird species. They provide nesting opportunities for birds, bats and more. Essentially, they add another element of complexity to a hedge making it a better habitat, capable of providing a home for more species.

- Hedgerow trees can be versatile to suit your needs. They can be managed for timber, wood fuel or additional crop production, they can be coppiced, pollarded or left to grow as standards.

- Hedgerow trees form ‘open grown’ trees with full canopies, which have huge ecological differences and advantages to trees grown in close proximity as in a woodland. Open grown trees can live longer, provide more and more varied habitat niches and are incredibly important for rare and endangered saproxylic species.

Possible compromises of hedgerow trees

Whilst there are obvious benefits for hedgerow trees, there are some situations where more may not be an advantage. There are some traditionally open habitats in the UK that will not benefit from increased tree cover, or even an increase of hedgerow length, so it is with considering the local area carefully before increasing tree numbers. Hedgerow trees can provide a perch for predatory birds, so it may not be appropriate to increase the number in sensitive areas with ground nesting birds.

If you have a single species hawthorn hedge, you may wish to consider the species of your hedgerow trees carefully. The full canopy of a mature oak will begin to thin a hawthorn hedge below it, as hawthorn is intolerant of shade. You can overcome this problem in a few ways;

Plant smaller species of trees with less dense canopies such as rowan, hazel, crab apple etc.

Establish hawthorn trees from the hedge itself, where appropriate, by leaving stems standing when laying. Hawthorn grows as a small tree and will not do the damage to the hedge that an oak might.

Diversify the hedge planting around the trees themselves; use shade tolerant species below the tree, such as holly or hazel. These species will tolerate the shade of a mature hedgerow tree far better than hawthorn would. This is a traditional approach seen widely in areas that have more species rich hedgerows, such as Devon, where you commonly find holly at the base of oaks (or old oak stumps nestled in amongst a hedgerow holly!)

Create a ‘dead hedge’ in any hedge gap that has formed as a result of shading, to maintain the habitat connectivity.

Large trees can have a shading effect on the crops within the field

Whilst this additional shade may suit livestock, it can cause crops to ripen at different rates, which can be problematic when it comes to harvest. These effects can be mitigated when planning new hedge trees; small tree species can be used in east-west hedges to reduce any crop shading impact. Larger trees are better on north-south hedges where their shade won’t affect the crops, but where they often provide the added benefits of wind protection.

Trees do not have to be evenly spaced along and across hedgerows. In fact there are merits of having a diverse spread, with some hedgerows having more, and others fewer. However, where there are a large number of trees in a hedge, this can make the management of that hedge more difficult. Routine trimming of such hedges can be more time consuming, with more raises of the cutting bar. Depending on the tree species and size, as well as the hedge situation, a high density of trees can also accelerate legginess in the hedge below, which may mean the hedge would be better managed on a shorter life-cycle and need more frequent rejuvenation than others.

The need for more hedgerow trees – historical context

Our hedgerows have fewer trees in them than ever recorded. This is due to a combination of hedge tree loss, as well as lack of new tree recruitment.

Sadly, we lost a huge number of hedge trees to Dutch Elm disease and we are in the process of losing more to Ash dieback yet we aren’t establishing enough new hedge trees to accommodate these losses. The lack of establishment is partly an accident of our current management; with regular mechanical trimming, there is little opportunity for a tree to breach the hedge line, except at pylon poles.

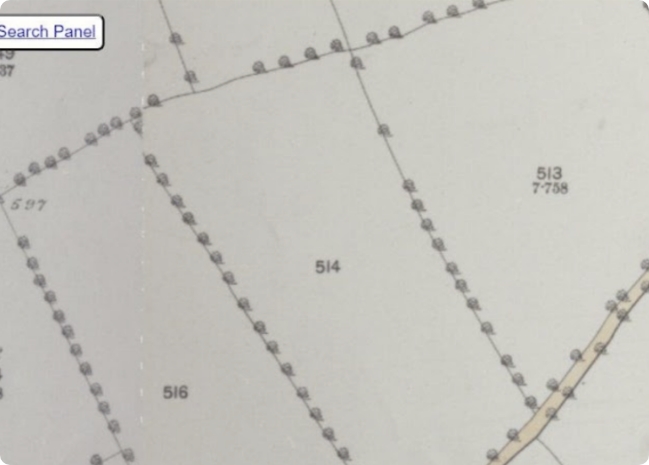

The left hand side of this image shows a piece from an old Ordinance Survey map, and beside it the satellite image of what this land is like now. Obviously we have lost a couple of hedges in there, but what is just as striking is the loss of mature hedgerow trees, individually indicated on the map, and almost gone as seen in the satellite imagery.

“To maintain the current population of 1.67 million trees 30,000 new trees need to be recruited to the population each year, whereas in fact only between 10,000 and 15,000 are. Urgent action is needed to address this shortfall if we are not to lose most of our hedgerow trees in the next few decades. To stabilise the hedgerow tree population 45% of trees should be under 20cm in diameter. Currently this figure is only 19%”

(Research commissioned in 2008 by Defra from Forest Research on behalf of Hedgelink)Hedgerow trees were historically an important source of wood and fuel

Hedgerow trees were historically an important source of wood and fuel, and we see the remains of fantastic hedgerow pollard trees still in our hedgerows today. These trees would have been cut at the same height above the trunk on a rotation and used for firewood and well as other uses. Today, these ‘lapsed’ pollards stand as relics in our hedges, a beautiful living reminder of our recent history whilst also an exemplary habitat for some rare and endangered species.

Whilst these lapsed pollards can be enormous, actively pollarding trees can be a good way of managing the size of your hedgerow trees.